Alzheimer’s Antibody Therapy Receives Accelerated Approval Amid Controversy

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) yesterday granted accelerated approval to the monoclonal antibody aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

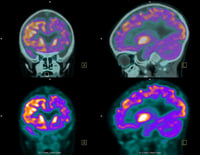

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by changes in the brain—which include beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles—that result in the loss of neurons and their connections.

“Currently available therapies only treat symptoms of the disease; this treatment option is the first therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s,” said Patrizia Cavazzoni, M.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA’s accelerated approval pathway is designed to speed up the approval of medications for a serious or life-threatening illness that provides a meaningful therapeutic advantage over existing treatments. The pathway enables drug companies to provide a surrogate biomarker that they believe can reasonably suggest future clinical benefit. In the case of aducanumab, accelerated approval was granted based on data from three clinical studies (including two phase 3 studies) demonstrating a significantly greater reduction of beta-amyloid plaques in patients with early stage Alzheimer’s disease who took aducanumab compared with those who took placebo.

The phase 3 data on the effects of aducanumab on cognition were inconclusive. Though one of the phase 3 trials found that patients who received aducanumab had a slightly slower cognitive decline than those who received placebo, the other phase 3 trial did not. In fact, an FDA advisory panel voted nearly unanimously in November 2020 that the clinical data supporting aducanumab were not sufficient to warrant approval.

“Under the accelerated approval provisions, … the FDA is requiring the company, Biogen, to conduct a new randomized, controlled clinical trial to verify the drug’s clinical benefit. If the trial fails to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may initiate proceedings to withdraw approval of the drug,” the FDA release stated.

The approval of aducanumab quickly sparked debate among clinicians, researchers, and advocacy groups. Many scientists believe that the approval—even conditional—is premature.

“The most compelling argument for approval was the unmet need, but that cannot, or should not, trump regulatory standards,” said Caleb Alexander, M.D., a professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University and member of the FDA advisory panel, in a news article. “It’s hard to find any scientist who thinks the data are persuasive.”

Malaz Boustani, M.D., M.P.H., the Richard M. Fairbanks Chair of Aging Research at Indiana University School of Medicine and a research scientist at the Regenstrief Institute, gave a more optimistic view in an interview with Psychiatric News. Though the data are not yet conclusive, he noted that the safety profile of aducanumab was favorable relative to other antibody-based medications such as those used in chemotherapy. Given the tremendous health care burden of Alzheimer’s, he said that he believes the benefit-harm ratio supported a conditional approval.

“I think this approval could also have a ripple effect in improving Alzheimer’s recognition,” Boustani said. “Currently, we miss anywhere from 50% to 80% of patients with Alzheimer’s because brain scans are not routinely provided as a standard of care.” Now that an early stage Alzheimer’s treatment exists, physicians may be more willing to recommend scans for patients, which can help confirm the type of neurodegeneration a patient is experiencing, he said.

For related information, see the Psychiatric News article “New Report Suggests Alzheimer’s Prevalence May Triple by 2050.”

(Image: iStock/wenht)